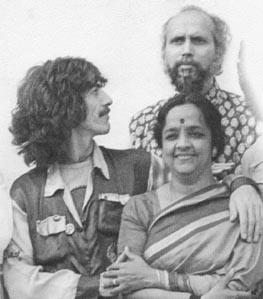

One day in tabla class - I studied on the side back in my scientific days at CalTech - some progressive-minded classmates and I, looking for a bit of spice and a bit tired of the (while often interestingly subdivided but still) powers-of-2 meters, goaded our teacher, Harihar Rao (top right), into amusing us with some rhythmic fireworks. Like all Westerners, we were always looking for something new and more exciting than what he was actually teaching us, never really willing to spend the time to learn the details of anything, like dancers seeming to hold their partners close but really looking past, scouting the next liaison across the room. But he had been teaching gringos like us for many years and so was used to this blasphemy and, with a weary acceptance, proceeded to teach us a somewhat complex 7 beat pattern. We then tried, a bit shakily, to keep this going, as steady as we could, as he straddled it with an 11 beat pattern, his beat effortlessly 11/7ths faster. It was a sweaty and joyous bit of concentration, collapsing and coming back together as we tried vainly to hold the two opposing rhythms in our head, to achieve what he could seemingly without thinking.

One day in tabla class - I studied on the side back in my scientific days at CalTech - some progressive-minded classmates and I, looking for a bit of spice and a bit tired of the (while often interestingly subdivided but still) powers-of-2 meters, goaded our teacher, Harihar Rao (top right), into amusing us with some rhythmic fireworks. Like all Westerners, we were always looking for something new and more exciting than what he was actually teaching us, never really willing to spend the time to learn the details of anything, like dancers seeming to hold their partners close but really looking past, scouting the next liaison across the room. But he had been teaching gringos like us for many years and so was used to this blasphemy and, with a weary acceptance, proceeded to teach us a somewhat complex 7 beat pattern. We then tried, a bit shakily, to keep this going, as steady as we could, as he straddled it with an 11 beat pattern, his beat effortlessly 11/7ths faster. It was a sweaty and joyous bit of concentration, collapsing and coming back together as we tried vainly to hold the two opposing rhythms in our head, to achieve what he could seemingly without thinking.For the few years I studied with Harihar, I couldn't walk anywhere without tabla rhythms appearing over the pulse of my step. It was an obsession, a compulsion. I would practice the patterns as I walked, like all drummers I have known since, making approximations of the sounds with my body, trying to fly each pattern against 3 beats, 4 beats, and 5 and 6 and on. The important thing - or what seemed so at the time - was to be able to perform it consistently while shifting one's concentration from one pulse to the other, flickering between views as with the Necker cube. Relative prime rhythms were of course the only ones that were interesting, like the relative primes that defined the intervals of which I was just becoming aware, and these rhythmic practices spilled out into my pianism, forcing me to play scales in polyrhythms, to add or subtract a beat or two or three to each measure of the left or right hand parts of just about anything to squeeze or expand them just a bit, a pleasant flurry of notes not quite lining up, like the middle bit of the first of the op. 28 Chopin préludes where the right hand switches from 6 to 5. [A note to the reader trying this at home: better is to move the right or left hand up or down a bit as well, a fifth or a third or whatever, and then, even better, to just stop playing other people's music as it's easier on the stereo anyway.]

I was lucky enough to attend CalTech when Richard Feynman was still teaching Physics X, and my friends and I would hang out there too, asking questions about the Moon and the blue sky and rainbows and gravitation and electron spin and DNA and the structure of the eye, learning more about science and its cousins in the barest refractions of light in the few smallest drops distilled from the great man's essences than in all of our more formal studies. The class wasn't really a class at all, but an informal seminar, held in the basement somewhere, maybe Lauritsen, where the students would ask questions about anything, attempting and failing to stump the great man, and where Feynman would always cut through to the heart of each issue, bringing an oh-so-pleasant shock of illumination and intuition.

CalTech was a strange and insular place, a tremendous opportunity for those who were prepared to take advantage of it, suicidally difficult for others, stocked with children who had been locked away, sequestered from society from birth by the nature of their interests and their antisocial smarty-pants disposition. But, even in that rarified place, where Nobel Laureates were dime-a-dozen, Feynman was an icon who floated a bit above the rest. When he showed up to our tabla class one day, we were suitably star-struck and tongue tied, unable to respond to his easy manner. His bongo playing was well-known to us, and well as some of his other idiosyncrasies - one I remember well is when he showed up at a meeting of the CalTech Christian students simply to point out what idiots they were for believing against all facts and logic - but in the end the instrument was beyond him, and he an old dog trying to learn a few last tricks, the sounds too subtle and he too impatient to coax them out of the hide.