Thursday, November 1, 2012

Science

In music, I love such nonsense. I think it is important somehow, like reading a kōan, putting the mind in a place where mere truth is irrelevant, but I also do have a deep lasting long term relationship with science - and maybe even a love for it - which goes back to my youth, discovering one day a large cache of old Scientific Americans and reading through them all from cover to cover and cardboard box to cardboard box. It leads me to still spend days reading through scientific and mathematical articles, scribbling down my own calculations and pondering the deep search for truth. Although I sometimes dissemble when discussing it, my doctorate is not in music at all, but in Electrical Engineering, and I recall a story from those days. My research advisor was Al Despain, a wild-haired crazy man who was willing to skim off some money from his various defense grants to support me, a poor graduate student interested in the intersection of music and technology in those heady times, when one had to write one's own file system to get samples off a disk fast enough to achieve audio rates, when one had to build one's own D/A converter to listen to the audio in real time. But Al's true love was all things military, and one day he told me to be at his house the next morning early, where we were met by a limo and, quickly chewing through several columns of Fig Newtons, headed to the airport and a quick flight to San Diego. Again, a limo, and bustled into a room, I found myself giving a talk on my thesis to a room full of JASONs, the notorious and/or acclaimed MITRE-related Defense Advisory Group, including the esteemed Freeman Dyson. I bumbled through, in awe, and wondered at the attendees most celebrated, not able to say what I really wanted to say: in fact some kind of gushing fanboy babble.

Last week, driving back from visiting my mother and my in-laws, I was reminded of this experience when listening to a Relatively Prime podcast on Paul Erdős. The subject is dear to my heart, and I glow with a very small respectability due to a paper I published with the mathematician Oscar S. Rothaus on Gaussian Residue Arithmetic, giving me an Erdős number of 5 to his 4. The podcast featured three mathematicians with Erdős numbers of 1, and one of them told how he was invited by Erdős to give a talk at a symposium where no one showed up except Erdős, the organizer of the symposium and Stanislaw Ulam, and how proud he was to give his talk to such a small but illustrious audience. In life and work, we love our icons and we hope that someday they may love us.

Friday, April 4, 2008

Luigi Dallapiccola

My son said yesterday that it would be expedient for me career-wise to spend a bit of time in prison, especially for a political crime. Maybe that's more likely currently, here in the land of Mussolini and Berlusconi than back in the sun soaked bliss of whatever San Francisco. In Roma my thoughts have turned to the various Italians I have known and loved: Nono and Berio and Dallapiccola. The budding latter young Luigi did spend some career enhancing time with his family in a camp for subversives in Graz, the hometown of our own favorite California National Socialist and Führer, but the connection today is a mention of myself in a discussion here on whether Dallapiccola may have wanted to have his music played in JI or some other non-equal tuning system. I felt compelled to correct a small error. A statement on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: I often need to correct others' mistakes, answer yes. JI and tuning history in general is still so misunderstood, and the recentness of the God-given nature of 12 equal so little known, that I do feel I need to say something from time to time just to rail against the darkness etc. Once again I feel the need to retune my life and music a bit.

My son said yesterday that it would be expedient for me career-wise to spend a bit of time in prison, especially for a political crime. Maybe that's more likely currently, here in the land of Mussolini and Berlusconi than back in the sun soaked bliss of whatever San Francisco. In Roma my thoughts have turned to the various Italians I have known and loved: Nono and Berio and Dallapiccola. The budding latter young Luigi did spend some career enhancing time with his family in a camp for subversives in Graz, the hometown of our own favorite California National Socialist and Führer, but the connection today is a mention of myself in a discussion here on whether Dallapiccola may have wanted to have his music played in JI or some other non-equal tuning system. I felt compelled to correct a small error. A statement on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: I often need to correct others' mistakes, answer yes. JI and tuning history in general is still so misunderstood, and the recentness of the God-given nature of 12 equal so little known, that I do feel I need to say something from time to time just to rail against the darkness etc. Once again I feel the need to retune my life and music a bit.

Monday, March 3, 2008

Meditation on Jon

Composing music is a strange ephemeral artform, constructing something from the almost nothingness of sound, pressure-wave vibrations of the air. But this strange ephemera is somehow able to touch deep inside the listener, bringing up emotions and reactions pleasant and unpleasant but impossible to ignore. In the films of the Hollywood mainstream, the emotional power of music and its ability to pass by the viewer's defenses is often used to manipulate, to subliminally broadcast to the listener how they are supposed to feel. But music in Jon's films is different. Although it carries a large part of the emotional weight of his films, it is not a hidden wedge into the viewer's heart. In fact, it is usually banished from those scenes which are the most directly narrative and kept to those long minimal moments of repose that are so dear to Jon. It is given an equal billing, with narrative, with the landscape, with the characters, part of a set of parallel threads that each relate to the viewer a different aspect of the story.

I first met Jon at a screening of All the Vermeers in New York at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley California. The producer, Henry Rosenthal, whom I had known through the Just Intonation Network years before, called me and told me I had to come, that it had been a labor of love and that he was quite proud of it. When I saw it, I was enraptured. I loved the look of it, the pace of it, the feel of it, and especially the music by Jon English. It was such a musical film, both indirectly, with a feel for rhythms on the short and long and architectural scale and directly, leaving space for musical development that Jon English filled so beautifully, especially in the long tracking shot dancing among the columns of the lobby of some Wall Street location.

A few years later, as Jon Jost's Sure Fire needed to be finished for its debut at Sundance, Henry called me while I was staying in a room in a businessman's hotel in Japan that was the size of a smallish shoebox and told me that Jon English was too ill to finish the music, in fact that he had written only a short melody for pedal steel; that the music had to be done in a couple of weeks; that it needed to be in a country style and that it also had to be in just intonation. I jumped at the opportunity. When I returned from Japan, I got a videotape of the film in its almost-finished state and wrote the music very quickly, sketching out a primarily synthesized score, starting from the melody that Jon English had written, and bringing in his pedal steel player to improvise with me. There were some brief meetings with Henry and Jon Jost, where they pointed at large problematic sections and told me to fix them, but mainly I was left alone to do what I wanted inside the constraints of no budget and no time. Jon did tell me there were some important numerological features of the film centering around the number 13, which I worked into various rhythms and various pitch ratios.

As Sure Fire was completed and as Jon and I spent more time together, we had an opportunity to work in a more relaxed fashion. He started to tell me of his plans for the next film, The Bed You Sleep In. Jon had written bits of a script and said that he wanted some music done before production so that he could play it for the actors while they were working. He also told me one of his recurring ideas, that he had always wanted music that naturally came from the location sound, sometimes imperceptibly. But he also wanted real music, not just sound, and I suggested a mixture of classical and folk and electronic instruments, and a mix of classical and popular styles.

From the notes to the CD:

During the production of the film, John Murphy, who was doing the location recording, took me into the sawmill featured in the film. Walking through the mill was like listening to a great industrial/futurist composition, the sound wonderfully dense and richly spatialized. The sounds and smells of the local mills, especially the Georgia Pacific plant, were present throughout the town of Toledo. The sound of the GP plant was audible in all the location recordings, whether inside or out. The plant sat at the side of a tremendous chemical lake, a dirty brown pool with fountains spraying noxious liquid in large plumes up from the surface. Its presence so overwhelmed me that, at one point, I had decided to do all the music using the sounds of the mill and the GP plant. In the end, I used a variety of sound sources. Some of the music, notably that which frames the letter scene, is generated almost entirely from sampled and processed recordings of the mill made by John Murphy during the production. Some of these samples are used as instruments in other pieces and are mixed with the acoustic instrumental ensemble. [...]

After the production, Jon and Mark Redpath started editing and I began to see the film that didn't exist in the screenplay. There were many long, static shots where Jon wanted the music to firmly imprint the film's bleak emotional state. There was an extensive use of split screens. There were a number of musical dichotomies I intended to be analogues of this, but the most successful [were in two scenes]. The first was a spare statement, where a single tone split into two diverging tones. In the second, where the screen collapses in on itself, a similar divergence occurred in a rich instrumental texture, causing the harmonies to quaver and shift in a continuous manner.

I went with Jon and Henry to the premiere of The Bed You Sleep In at the Berlin film festival where, unfortunately, Jon and Henry had a falling out over disagreements about control and ownership of the films they had done together. By the time Frame Up was completed, for which Jon English wrote the music and I did some sound work, the two of them were completely separated. But, in late 1994, Jon asked me to come to Vienna to begin work on Albrechts Flügel, a film about a second violinist in the Wiener Symphoniker, a person who, like so many of us, comes close to greatness, almost achieving it, but who is painfully aware that they will never succeed. It is so sad to me that this movie never came to fruition. The music was to have been an integral part of the film, part of the narrative and a lens through which the characters saw the world. Jon and I talked many times about the music and the ideas in the film. I worked with one of the actors, an amateur violinist, and I started to work on some music, including what became the Albrechts Flügel suite of piano pieces. This, I thought, would be the next step in our artistic relationship, a close partnership from the beginning of the film, hinted at in Bed, but taken even further. But the film fell apart when Jon discovered some irregularities in the handling of the financing for the film. I was never clear exactly what happened, but he left Austria and settled in Rome, where he finished Uno a me, uno a te e uno a Raffaele.

Soon after, Jon turned away from narrative films, playing with the flexibility and affordability of cheap digital cinema, first with Nas Correntes de Luz da Ria Formosa, a beautiful meditation on a fishing village in Portugal, and later London Brief. I worked with Jon on the latter film, but only from a distance. I wrote a number of pieces, all electronic works, based on what I saw in his early drafts. I gave him a free hand in using those excerpts, placing them where he wanted, cutting and adjusting them. I know he liked the intimacy and control of the new medium, that he could sit and work and recut and change everything at his computer by himself without having to worry about cutting room rental costs, sound engineers, and so on. I think, in his heart, Jon wishes he could do it all himself. He wrote the music for some of his early films and has a strong musical sensibility and, finally, is a person with a strong overall vision.

Since that time, I have contributed music for a couple of his films after his return to narrative filmmaking: Homecoming and La Lunga Ombra. I'm sure that, sooner or later and his recent cancer scare notwithstanding, I'll do more. But because of our separation - Jon is in Korea these days - and the lack of money available for Jon's work and therefore for my time, there hasn't been quite the same level of connection as when we did Bed and Sure Fire, when we used to play table tennis together (Jon and I are both very competitive) and talk in detail about the films and how the music should act in them. Maybe it can happen again. I hope it does.

photo by mica scalin

Monday, October 29, 2007

Or we will all die

I've been meaning to mention Jarod DCamp's new microtonal radio station 81/80, aptly named after the comma of Didymus, one of my most favorit-est intervals, appearing in a melody in Tune for Lynn Murdock #2, at least as I remember. The radio station is a great source of serendipitous discovery, a very eclectic set of tunes showcasing a wide variety of styles, putting paid to the oft-said notion of the microtonal 'style.' The station features a number of people I've met over the years, plus all those who came after I stopped paying as much attention, and the web site seems to have an old picture of me by Debra St John. Note that Kyle Gann has blogged the station and we would all do well to search in this entry for the current blog title and read the surrounding paragraph. I myself have promised to do a little tuning up of the Mordake opera.

I've been meaning to mention Jarod DCamp's new microtonal radio station 81/80, aptly named after the comma of Didymus, one of my most favorit-est intervals, appearing in a melody in Tune for Lynn Murdock #2, at least as I remember. The radio station is a great source of serendipitous discovery, a very eclectic set of tunes showcasing a wide variety of styles, putting paid to the oft-said notion of the microtonal 'style.' The station features a number of people I've met over the years, plus all those who came after I stopped paying as much attention, and the web site seems to have an old picture of me by Debra St John. Note that Kyle Gann has blogged the station and we would all do well to search in this entry for the current blog title and read the surrounding paragraph. I myself have promised to do a little tuning up of the Mordake opera.And, by the way, changed the color scheme on my website to match a newfound interest in truth, honor and transparency.

Saturday, May 26, 2007

Tuning Troubles

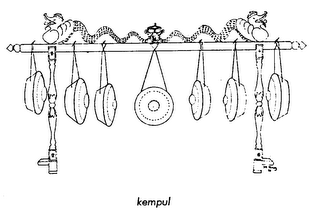

When I first started playing in a Javanese gamelan, it was difficult for me to get past the tuning, the unfamiliarity of which got in the way of understanding the music. In fact, it was so difficult for me in those first few days that that I didn't even get that I wasn't understanding the music. This was a little unexpected for me, as I was already very familiar with tuning experiments in modern classical music. For example, I had listened to a lot of quarter tone music and, at that time, I was working on a somewhat ridiculous piece, a concerto for contrabass accompanied by a trombone quartet and choir, where each section of the ensemble used a different fixed-pitch equal-temperament, e.g., chromatic scales of 1/8th tones and 1/6th tones and so on. The chorus was used like an orchestra, singing various IPA-notated phonetic abstractions. But I was raised on the serial music of the world of the post second Viennese school, was intimately familiar with the sound of it, had an intuitive grasp of it and this just seemed like a logical way to go forward. But the gamelan was different.

When I first started playing in a Javanese gamelan, it was difficult for me to get past the tuning, the unfamiliarity of which got in the way of understanding the music. In fact, it was so difficult for me in those first few days that that I didn't even get that I wasn't understanding the music. This was a little unexpected for me, as I was already very familiar with tuning experiments in modern classical music. For example, I had listened to a lot of quarter tone music and, at that time, I was working on a somewhat ridiculous piece, a concerto for contrabass accompanied by a trombone quartet and choir, where each section of the ensemble used a different fixed-pitch equal-temperament, e.g., chromatic scales of 1/8th tones and 1/6th tones and so on. The chorus was used like an orchestra, singing various IPA-notated phonetic abstractions. But I was raised on the serial music of the world of the post second Viennese school, was intimately familiar with the sound of it, had an intuitive grasp of it and this just seemed like a logical way to go forward. But the gamelan was different.My music at the time was not really harmonic, essentially percussion music with a pitch veneer slathered on top, disguising its true nature. I mean, it was harmonic in the sense that pitches were sounding at the same time as each other, and sometimes the harmonies were exciting and beautiful, but it wasn't really part of the overall architecture of the piece. So when I was confronted by music where the tuning was different but the music was straightforward - in the sense that it was not intended to be difficult to understand and was supposed to have an immediate emotional impact and leave you humming the tunes - the tuning was a wall that took a few days to get past. However, once I did, I fell in love with it, could sing along and could find the pitches easily and felt that they were, in fact, quite "correct." I wanted to comprehend this feeling and apply it in my own playground of pitches. I felt that I was missing something important and possibly following the wrong path.

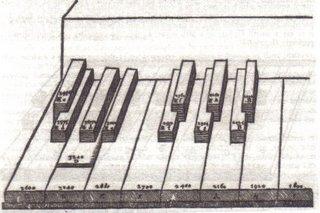

The next surprise came, though, when I found that the gamelan pitches were not systematic. Each gamelan, while following some general guidelines about large and small intervals, was tuned quite differently. Bill Alves has a lovely set of graphs of tunings of some of the well-known gamelan from Central Java. The somewhat mythic story that was given to me by my teachers at the time was to the effect that, before a new gamelan was built, the builder would go sit on a mountaintop until the tuning came to them in an epiphanic moment, at which point they would build the first instrument and then copy the tuning of it for the others. I realized that my own experiments in tuning had been extremely constrained, in addition to having failed to arrive at any type of real "truth," whatever that might be. So my friends and I started building a lot of instruments with random tunings, cutting pieces of wood and metal to random shapes, laying them out in xylo/vibraphone-like arrangements in pitch-sorted order and then writing music using these pitches. It was amazed how quickly these random tunings sounded 'OK' and how they seemed intuitively to yield an appropriate music.

But, at the same time, I was discovering that the American gamelan builders were basically all using Just Intonation. Why exactly, given that the intuitive tunings of the Southeast Asian gamelan seemed like a possibly critical aspect of the whole music? Didn't this miss the point? I wasn't sure, but JI scratched my analytical mind's itch, that which was demanding some sort of organizational scheme for all the possible pitches. I had a little familiarity with it already. I had heard Harry Partch's music in my youth and I knew from my history of mathematics that solving the "problems" of JI had been a major preoccupation among the intellectual elite for a long time. I read Partch's book and I hooked up with the Just Intonation Network and this did help me get a handle on my pitch universe, or maybe I should say my interval universe. But, being an old dissonance guy and a sensation slut in general, I didn't get caught up in the pseudo-mystical nervousness about purity of intervals and the monotony of beatlessness. I liked the wolf tones, the odd intervals, the sweet edges of schismas and commas. And it didn't really deal with all my pitch issues anyway, e.g., glissandi and vibrato and the three strings on each key of the piano. (My JI friends' response to these issues? Don't use vibrato, don't use glissandi, don't etc etc.) (My noise music friends' response to everything I've been talking about? Who cares about pitches?)

The funny thing that happened on the way to this perfect universe of pitch complexity is that I started writing more and more tonal music. Thinking about intervals has a poisoning effect that way. It makes one think about roots and centers of intervallic grids. And then, in the end, I dropped the tunings and just found myself back in the usual world of more-or-less equal temperament. In the end, tunings were too socially isolating, too difficult given limited rehearsal times, too off-putting to the casual listener. My new opera, Mordake, is an all electronic piece and I could use any pitches I want, but I'm still shying away, fearing the impediment to the listener. It's hard enough to get people to listen; I don't want to make it more difficult for them. But then, maybe I should.

Musique Arabo-Andalouse

Thinking of the jet of water reminded me of an aborted project to write an opera based on Artaud's Jet of Blood, causing me to stumble across this lovely Australian production of this unproduceable piece.