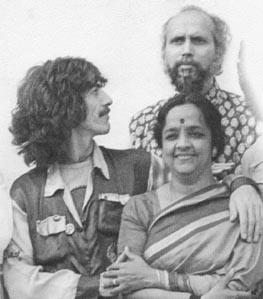

Clark Suprynowicz

Clark Suprynowicz and I were talking opera libretti recently at a fundraiser for the John Duykers and

Miguel Frasconi work-in-progress,

Hand to Mouth: The Journey of the Seed from Soil to Plate, a opera-ette which draws on John's other career as organic farmer and nearly-organic beekeeper, and the fact of our divergent approaches made got me to thinking. I'm a prose man, and believe in the sanctity of the language, which is typically my entrée into a text-based piece. To reiterate, language is the key to an opera composition, the way in, containing something that strikes me as being musical, in whatever sense one takes that. I've been considering

Queer again lately, as we are planning to remount that in the Spring of 2011 as the 10th anniversary of the premiere and the 25th anniversary of the book's publication. Burroughs's writing is very musical, its flow and lilt and repetitions and its connection straight to the gut, not poetic in the old-fashioned sense of meter and foot, but its music inspired my own. In comparison, Clark's cavalier attitude to what his librettists have written down, and the fact that he bends their words to fit his tunes, seem quite sinful. For me, tunes and music spring from the words, although I hope that the music isn't simply painting colors over the words and that the music that comes from this interaction can stand on its own. I remember being asked once by a singer during the development of an early piece which sections were recit and aria and I realized it hadn't even crossed my mind. I was presenting the text, and I suppose some sections fit one label or the other, that some were internal monologue, outside of the action, and some were more action oriented, but I didn't stop somewhere along the way to sing a song, a song with a melody upon which the words were hung.

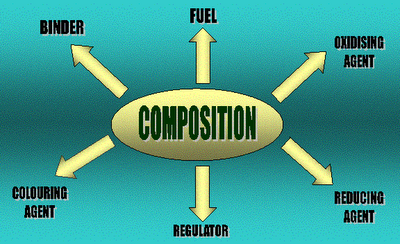

When I first studied composition, way back when, the very first exercise we did was to set a text and I've realized this may have shaped my approach early on. We each chose a poem and analyzed it, reciting it several times, writing down the rhythmic result in sprechstimme form, trying to capture the prosody and also the pitch contour of our recitation. The teacher's idea was that this was necessary to understand simply where the musical stresses should fall, and what the melodic pitch contour should be to properly capture the sound of the poem. But I realized in a moment of youthful revelation that this scribbled down proto-setting was the nut of the piece to come, that I could distort this pitch function of time in a number of ways, stretching it and shrinking it uniformly or non-uniformly in either axis, translating it, a whole series of affine and even nonlinear transformations, but that this would really be the piece, what the audience heard, my translation of the poem to sound.

When a composer sets text, the composer is the actor, is the reciter, and no matter who performs the piece thereafter, even though they may emote and express, they are fundamentally locked into the actor-performance of the composer herself. The composer locks down the basic timing and puts the reaction of one actor to the other into the mouth of each. The funny thing is, very few composers are taught acting or reciting or anything remotely theatrical or dramatic. We could ask, why should their conception of the text become the one true path through it?

I noticed something in my first piece which had real actors, A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil. Professional actors, who had no problem memorizing long monologues from traditional plays, were suddenly thrown off balance when they had to say their piece over a fixed length of time - to fit with some music and arrive at some dramatic point at the right moment. They stumbled and forget their lines and couldn't remember their stage business or act natural. Their whole acting lives had been all about the fluidity of time and expression and reacting to the moment, reacting to other actors, working in a development process, sometimes over a long time, sometimes with a director, to figure out their best pacing and timing and then to improvise some of those things further during performance, like real life. But the simple request to fit that expression into a certain stretch of time, combined with fighting against the rhythms of the music behind them, broke them down. So what to say about opera singers for whom almost all of these actor-ly expectations are subverted? Does this explain why opera in its heyday, pre subtitles, fascinated by its golden age, almost ignored the text completely, concentrating on the beautiful line, the voice, all the actors standing on the edge of the stage singing to the audience and ignoring each other, the audience swooning and crying, only knowing what is going on from the fact that they had seen the piece over and over and over and had the story synopsis in their program?

I tried to do something different in

Mordake to alleviate this, playing with a technological solution, where John could sing a line freely - where he could

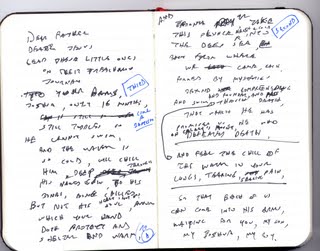

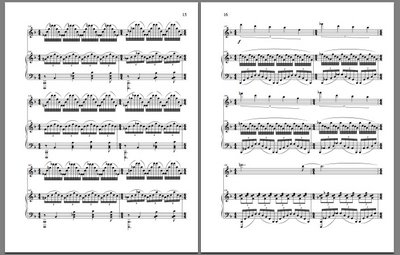

act - and I would have fiddle with the knobs of the accompaniment, lengthening and shortening the music underneath to fit. I failed to achieve what I wanted, partially because I'm into dominance and control, but also because I think it would have required some more radical changes to my own compositional process. The fragment at the top of this post is typical for me, meters changing to fit the textual rhythm, and that has defined so much of who I am compositionally. I was recently reading an

article by Kirke Mechem on choral setting, which is a different animal than opera, as the audience's understanding of the words being not so critical. In this piece, he talks about the importance of musical form, and once I got past my usual reaction in hearing the phrase "musical form," which is to release the safety on my Browning, I realized that I agreed with him, text setting shouldn't be, as he says, the musical equivalent of painting by numbers, but I also realized that all the text setting I have done has changed my notion of musical form. My later instrumental works sound to me like little operas, not that they actually have an underlying story, say

Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, but they seem dramatic, wandering along and telling a tale, the music unfolding from what has come before, with asides and interjections, and me making the same kind of dramatic decisions: should there be a climax here, time for the intermission, or for the audience to relax and whisper and kiss their neighbor, am I going to go for the slam bang ending or the whimper, is it time for love interest to arrive? But Kirke did walk out in the middle of my opera

Sub Pontio Pilato, brought there by his son and my good friend Ed, whose birthday was yesterday, and with whom I made out briefly for the amusement of his girlfriend and other guests on Sunday, me always willing to give a hand up to my friends, so maybe he didn't agree with my approach and thought my form was lacking, and who can see into the heart of another?

an UPDATE from Ed:

Just for the record, I believe (and I *was* sitting there with him) that he 'walked out', ahem, during intermission, because his back was hurting him. If you want to, ahem, add a little footnote to your post, detailing the dry boring reality (in contrast to the dramatic characterization!) -- feel free :)

OK, well, that is much drier and less colorful so not as interesting, but is the truth.