While searching on post minimalism in music, I quickly came across the seminal essay by Kyle Gann from '98. It's a good read, and I'm in the camp of believers - believers that it existed that is - mainly because of the disconcerting fact that his post describes me well. One likes to think that one arrived at one's place in life by one's own decisions, one's own will, one's own process, but the reality is that one is swept along by the currents of history. I too was raised a believer in modernity, a believer in the goodness of complexity, and I too had the Damascene conversion while listening to Einstein on the Beach in the late 70s. I too can't shake off the old feelings while embracing the new and I too was led to the same places: rhythm and accessibility and tonality-with-an-edge.

It reminds me of a story that I believe Jim Bisso told me about his Palestinian friend asking him what religion he was, to which Jim replied atheist or whatever and his friend then saying no no no, what religion are you? I mean, what religion were you born into? That's a caste you cannot change. We put on the coat of our place and time and culture and family. I am the composer I am because I am here now and that's a choice I cannot unmake.

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Monday, June 18, 2012

The Opera Conference and its discontents

Finished the Opera Conference 2012 in beautiful Philadelphia, having gone in partial settlement of a debt to Opera America for all their help over the years. Grant awards that I assume were sized as moderate assistance to a major company have been to me lifesavers: major assistance to my micro-sized company.

It was a wonderful and eye-opening experience. Clearly the tides of opera have turned since I first joined in the late 90s. Back then, the Opera America Magazine's list of upcoming opera productions of the major companies would be the same every issue, changing only in which company was assigned to which opera. Which reminds one of the story of John Cage during the writing of the first Europera, being allowed into the basement library of the Metropolitan Opera, where he expected to find a vast array of scores covering the history of the art form but was surprised to find only a few handfuls, as really that was all that was necessary year by year. Now, however, companies are scrambling to present new works, either in main stage high-profile commissions, or second or third or Nth productions of smaller or exotic works that have picked up some press, e.g. the famous-for-its-humjob Powder Her Face, or the moving Nico Muhly opus Dark Sisters, the latter of which was presented at the conference, and is in the seemingly growing genre of operas about the complexities of faith.

To an extent, this sea change is due to a die-off of the Old Guard - a descriptive phrase used publicly during the conference - as well as a growing understand of the Death Spiral, to wit, cutting budgets and doing the same-old same-old and finding your ticket income dwindling and then cutting back more and round and round. As for the pilot of a small Beechcraft caught in a tailspin plummeting to earth, one needs to pull back on the stick as it were, and The Way that has been determined to accomplish this is the development of new pieces. Which might possibly be good for those of us who have been doing it. Possibly.

Some high points: the neon-overloaded Geno's vs the tradition-beloved Pat's Cheez Whiz® slathered steak competition, the Mütter museum, the call from Kent Devereaux to talk about coming up to Cornish to teach the young tykes only to find out that we were 50 feet from each other, the walking around the downtown, the kindness of the people of Philadelphia, the Philosophical Society, a bunch of interesting people from staff members of Opera America to producers to opera lovers and kooks and rich folk, the endless drinking, the Persichetti memorial, the follow-on trip to New York for the Bang on a Can Marathon and the visits with more friends, and a lovely meeting with the powerful, intimidating but also quite inviting Beth Morrison.

In the picture above, I am praying. My prayers may be answered. Time will tell.

It was a wonderful and eye-opening experience. Clearly the tides of opera have turned since I first joined in the late 90s. Back then, the Opera America Magazine's list of upcoming opera productions of the major companies would be the same every issue, changing only in which company was assigned to which opera. Which reminds one of the story of John Cage during the writing of the first Europera, being allowed into the basement library of the Metropolitan Opera, where he expected to find a vast array of scores covering the history of the art form but was surprised to find only a few handfuls, as really that was all that was necessary year by year. Now, however, companies are scrambling to present new works, either in main stage high-profile commissions, or second or third or Nth productions of smaller or exotic works that have picked up some press, e.g. the famous-for-its-humjob Powder Her Face, or the moving Nico Muhly opus Dark Sisters, the latter of which was presented at the conference, and is in the seemingly growing genre of operas about the complexities of faith.

To an extent, this sea change is due to a die-off of the Old Guard - a descriptive phrase used publicly during the conference - as well as a growing understand of the Death Spiral, to wit, cutting budgets and doing the same-old same-old and finding your ticket income dwindling and then cutting back more and round and round. As for the pilot of a small Beechcraft caught in a tailspin plummeting to earth, one needs to pull back on the stick as it were, and The Way that has been determined to accomplish this is the development of new pieces. Which might possibly be good for those of us who have been doing it. Possibly.

Some high points: the neon-overloaded Geno's vs the tradition-beloved Pat's Cheez Whiz® slathered steak competition, the Mütter museum, the call from Kent Devereaux to talk about coming up to Cornish to teach the young tykes only to find out that we were 50 feet from each other, the walking around the downtown, the kindness of the people of Philadelphia, the Philosophical Society, a bunch of interesting people from staff members of Opera America to producers to opera lovers and kooks and rich folk, the endless drinking, the Persichetti memorial, the follow-on trip to New York for the Bang on a Can Marathon and the visits with more friends, and a lovely meeting with the powerful, intimidating but also quite inviting Beth Morrison.

In the picture above, I am praying. My prayers may be answered. Time will tell.

Saturday, May 26, 2012

home, with illustrations

I've been asked to write a song for the OPERA America songbook in commemoration of the new National Opera Center. They originally wanted words that would "celebrate the opening of a new home." This subject, though sentimental, connected with my sentimental nature, and brought forward memories of moving back and forth between the Sun-soaked White Middle Class sections of Southern California and the Scandinavian-soaked Far Northern White Midwest in my youth. Even though the commissioners seemed to back off from the theme later, expanding it to include songs about the joy or singing or whatever, I pushed forward in the original key.

When I was seven, we moved to the house in Grand Forks shown in the photo - the parsonage - as my father was the minister of the major Lutheran church in town. It was a home perfect for a young imaginative child, a house laden with a servant's quarter in the attic that could be buzzed from anywhere in the house through an electric buzzer system, a secret back staircase from the library or the kitchen up to said quarter, a walk-through pantry with a screened potato and bread store naturally chilled, a vestibule for the removal of snowy clothes - always unlocked but leading to a locked door and doorbell inside, a grand staircase to a landing with a built in padded bench lit by the sun and ideal for reading pulp science fiction, a suite of rooms looking over a mini-atrium-esque entry hall. And, in the basement, a room with large cartoon characters beautifully drawn. I hadn't been back since I left at the age of twelve, but I forced Lynne out on the road to visit it in the deep winter a year ago and, as the temperature dropped to frigid, I was invigorated. As Viking ancestral senses settled upon me, and the soft parts of me were left behind, the memories of the smells and sounds and sights of the way things used to be came back. I had written the current owners, who were gracious on our arrival, who took us in and toured us through their revisions. The woman of the household was curious to find what I knew of the house's history, which wasn't much, but she was fascinated to find that I made the drawings in the closet upstairs.

So then, my poem - or the lyrics as we say in the song biz - imagine a young girl moving into the house in some distant future and experiencing all that has been left behind by those who came before.

Home, with illustrations

A young child comes home from school, lifts the latch, and steps inside, shaking off the snow.

She dreamed of this house before she moved here. In her dream, there was a special room, just for her, deep down a disguised staircase behind the stairs. When she and her family arrived, she couldn't find a way to it. But still, she hopes that someday she will.

Looking, she finds her father, sitting at his desk, reading to himself: Kafka, old sermons, documents with notary stamps. He smiles to hear her. He turns.

When you live in a new place, you become a new person. It becomes part of who you are. Watching, remembering each one who lived there, their lives, each life.

An example: a boy who lived there long before drew pictures, like old cartoons, back when the Sunday comics were printed so large, two to a page; drew pictures on the wall in a part of the closet hard to reach.

Sitting in the sun, she daydreams and remembers squeezing herself in, feeling the walls the way he felt them, head craned forward to see.

In her reverie, she composes a poem:

How old is he now?

Is he crying?

Perhaps he thinks of me

The way I think of him

The little girl who has followed him

Into this house

The house thinks of us

And wonders

Listening in its slow way

To the sounds of the small city

Of the way we stay so close

Inside the warmth of each other

And the warmth of this home

She thinks back to the cold bright sunny day they moved in, the end of a long drive, the snow drifting so high that she could slide down it from the second story window.

Labels:

beauty,

composition,

music

Monday, May 14, 2012

УКСУС (UKSUS), an OBERIUper in 4 boxes

I've been commissioned to write a new opera for the Klagenfurter Ensemble, who premiered the German version of A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil years ago. I love them. So far, all I know is that it will start on or about the 30th of November 2012 and will run for 10 performances through December, which means Xmas for me in Austria, where the little children are put into bags and the young girls are beaten with sticks by the teen boys in Krampus costume. The piece is based on the works and to a smaller extent the life of Daniil Kharms and his fellows in the Russian absurdist collective OBERIU (The Association for Real Art). The libretto and direction is by Felix Strasser & Yulia Izmaylova, music by me. A cast of 2 women and 2 men, a band of 5 instruments, something like a jazz ensemble.

Many of Kharms's works are very short, for example:

A certain old woman fell out of a window because she was too curious. She fell and broke into pieces.

Another old woman leaned her head out the window and looked at the one that had broken into pieces, but because she was too curious, she too fell out of the window — fell and broke into pieces.

Then a third old woman fell out of the window, then a fourth, then a fifth.

When the sixth old woman fell out, I became fed up with watching them and went to Maltsevsky Market, where, they say, a certain blind man was presented with a knit shawl.

A number of these are included completely in the libretto and have the feeling of dark children's stories. In fact, after he died in a psychiatric institution during the siege of Leningrad and his avant-garde works were suppressed, he was known quite well as a children's book writer. Children, like me, are in love with nonsense, even dark and brutal nonsense.

Many of Kharms's works are very short, for example:

A certain old woman fell out of a window because she was too curious. She fell and broke into pieces.

Another old woman leaned her head out the window and looked at the one that had broken into pieces, but because she was too curious, she too fell out of the window — fell and broke into pieces.

Then a third old woman fell out of the window, then a fourth, then a fifth.

When the sixth old woman fell out, I became fed up with watching them and went to Maltsevsky Market, where, they say, a certain blind man was presented with a knit shawl.

A number of these are included completely in the libretto and have the feeling of dark children's stories. In fact, after he died in a psychiatric institution during the siege of Leningrad and his avant-garde works were suppressed, he was known quite well as a children's book writer. Children, like me, are in love with nonsense, even dark and brutal nonsense.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Annotations 2 (with Illustrations)

I've been reading Laura Wittman's The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Modern Mourning, and the Reinvention of the Mystical Body, and it has reminded me of my love of the accoutrements of academic writing: introductions, forewords, terminology ('bellicist'), the overuse of the inverted comma, and most especially, the notes. I love them. To read the notes - the many many pages of notes - is to see the strata of the study, cut across the page like layers of rock thrust up along a fault. And why are they there in such quantity? Merely to entertain readers like myself? Or only to protect one from the terrifying charge of plagiarism?

It's unfortunate that, in music, it is difficult to provide something analogous: a stream of musical and textual references that flow with the performance, guiding the ear and mind to the proper references. For example: "when I wrote this passage, I was stirring my tea, thinking of the phlogistonic diffusion of the heat, liquid-like, flowing combustibly through the metal of the spoon, from tea to thumb to painful pointing finger." Or: "I purloined this set of harmonies from such and such, except I added a few and used them in reverse fashion."

But, now that I read this, I think maybe it wouldn't be so interesting, or at least not interesting enough. But let us press on.

When I wanted to write of the young LaShaun/Erling, I wanted to put it in her voice. Two things came to mind: the baby tuckoo section of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and this passage from How We Write: Writing as Creative Design, which recounts a story written by an actual young person. Note the mixing of stories and that some important elements are missing:

My, that reads an awful lot like this unfootnoted and clearly plagiarized section of the libretto:

and that is what I used, again unfootnoted and unquoted:

Oh, and up top, the "layered representation of the Lorentz transformation" of my friend Logan. On his neck reads: Una salus victis nullam sperare salutem [the only safe bet for the vanquished is to expect no safety].

It's unfortunate that, in music, it is difficult to provide something analogous: a stream of musical and textual references that flow with the performance, guiding the ear and mind to the proper references. For example: "when I wrote this passage, I was stirring my tea, thinking of the phlogistonic diffusion of the heat, liquid-like, flowing combustibly through the metal of the spoon, from tea to thumb to painful pointing finger." Or: "I purloined this set of harmonies from such and such, except I added a few and used them in reverse fashion."

But, now that I read this, I think maybe it wouldn't be so interesting, or at least not interesting enough. But let us press on.

When I wanted to write of the young LaShaun/Erling, I wanted to put it in her voice. Two things came to mind: the baby tuckoo section of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and this passage from How We Write: Writing as Creative Design, which recounts a story written by an actual young person. Note the mixing of stories and that some important elements are missing:

One day in the street, a man was talking about Jesus. The sun was so bright it hurt the little girl's eyes. She was going to school and her grandma said take this lunch money. The man was talking to everyone, telling them what to do. But she knew that it was too much and she spent some of it. She was afraid of the man. When she got to school the teacher said where have you been. The girl said nowhere sorry. The light was bright behind his eyes. At home she took the toy out of her pack. The man told her to buy it. Her mama said go to bed so she did.Ahem. Cough. I can only say I am heartily sorry for these my offenses. And also for those to come. When I came to write the music for the my chosen section, I had a thought, a thought of a structure reminiscent of the openings of these two works:

Oh, and up top, the "layered representation of the Lorentz transformation" of my friend Logan. On his neck reads: Una salus victis nullam sperare salutem [the only safe bet for the vanquished is to expect no safety].

Labels:

certitude and joy,

music,

opera

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

The binding of Isaac

One day, God decided to test Abraham. God spoke to him: “Abraham,” and Abraham replied “Yes, here I

am.” God then commanded: “Take Isaac, your son, whom you love more than anything in the world, to the

land of Moriah, to a place on a mountain that I will lead you, and sacrifice him, kill him with a knife and

burn his body, the body of Isaac your own son, as an offering to me.” At this point, the author of Genesis

relates not whether this command concerned Abraham, reporting only that the next morning Abraham rose

early, cut some wood, loaded up his donkey and took Isaac and two servants out on the road.

One wonders what were the subjects of their conversations while sitting by the evening fire sharing a meal before sleep. Was Abraham jovial with his son, his favorite, the boy he dandled on his knee and raised to adulthood, his only son with Sarah his most belovèd wife, or was he more reserved, thinking of what was to come?

When asked how her day had begun, the day she was to sacrifice her children, LaShaun Harris related that, when she awoke, she received instructions to give her baby to Jesus, to give up her children as a living sacrifice. She was told to get dressed and to take her children to the pier, a pier she remembered from a trip long before.

After three days, they reached a place from where they could see the mountain in the distance, and Abraham told his servants to wait with the donkey while he and Isaac walked on, misleading them to believe that the father and the son were to pray and return. Unlike Abraham, LaShaun did not dissemble, and stopped by her cousin Twanda’s to tell her of her plan to throw her children into the water. Abraham gave Isaac the wood that Abraham was planning to use to burn his son’s body after he killed him, and Isaac carried it up the mountain. There is a similarity here, in the carrying of the wood, to the carrying of the cross by Christ, and there is something sinister here, the father placing such a load upon his son, while the father carries the knife and the fire.

Possibly sensing the strain in their relationship, Isaac turns to his father and asks: “Father?” – “Yes my son?” – “The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?” We see the rising confusion here: a three-day journey taken without explanation, taken with all the accoutrements of a ritual but without the object of said ritual. But once again Abraham prevaricates and says: “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.”

The appeals document in the Harris case is a curious read: an attempt to explain the unexplainable. Society wants to label her clearly, to isolate her so that we are to not to be infected by her malady. The legal terminology used throughout is quasi-scientific, and the text breaks down into a Linnaean taxonomy of argument: rebuttals and surrebuttals from experts all in the field of the human psyche, a field that we know deep in our hearts allows for no real expertise, not a science, not even an explanation, but merely a way to classify, to categorize, and by so doing hoping to hold the real issues at bay.

Finally they arrive at the mountain. We are told that this is the place that God had told Abraham about originally although, in the story, God has been absent since his original decree. And, in fact, without any further orders beyond those of three days before, Abraham builds an altar, arranges the wood on it, and then binds his son to the altar, on top of the wood with which his body is to be burned.

One wonders what were the subjects of their conversations while sitting by the evening fire sharing a meal before sleep. Was Abraham jovial with his son, his favorite, the boy he dandled on his knee and raised to adulthood, his only son with Sarah his most belovèd wife, or was he more reserved, thinking of what was to come?

When asked how her day had begun, the day she was to sacrifice her children, LaShaun Harris related that, when she awoke, she received instructions to give her baby to Jesus, to give up her children as a living sacrifice. She was told to get dressed and to take her children to the pier, a pier she remembered from a trip long before.

After three days, they reached a place from where they could see the mountain in the distance, and Abraham told his servants to wait with the donkey while he and Isaac walked on, misleading them to believe that the father and the son were to pray and return. Unlike Abraham, LaShaun did not dissemble, and stopped by her cousin Twanda’s to tell her of her plan to throw her children into the water. Abraham gave Isaac the wood that Abraham was planning to use to burn his son’s body after he killed him, and Isaac carried it up the mountain. There is a similarity here, in the carrying of the wood, to the carrying of the cross by Christ, and there is something sinister here, the father placing such a load upon his son, while the father carries the knife and the fire.

Possibly sensing the strain in their relationship, Isaac turns to his father and asks: “Father?” – “Yes my son?” – “The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?” We see the rising confusion here: a three-day journey taken without explanation, taken with all the accoutrements of a ritual but without the object of said ritual. But once again Abraham prevaricates and says: “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.”

The appeals document in the Harris case is a curious read: an attempt to explain the unexplainable. Society wants to label her clearly, to isolate her so that we are to not to be infected by her malady. The legal terminology used throughout is quasi-scientific, and the text breaks down into a Linnaean taxonomy of argument: rebuttals and surrebuttals from experts all in the field of the human psyche, a field that we know deep in our hearts allows for no real expertise, not a science, not even an explanation, but merely a way to classify, to categorize, and by so doing hoping to hold the real issues at bay.

Finally they arrive at the mountain. We are told that this is the place that God had told Abraham about originally although, in the story, God has been absent since his original decree. And, in fact, without any further orders beyond those of three days before, Abraham builds an altar, arranges the wood on it, and then binds his son to the altar, on top of the wood with which his body is to be burned.

Was Isaac obedient? Did he keep silent?

From the testimony of Yashpal Singh: The defendant was chasing the oldest child and taking off his clothes;

he was shouting, "No mommy, no mommy." Another child was sitting on a bench and a third child was

either in the stroller or on the bench. Defendant caught up with the oldest child, Trayshawn, and brought

him back to the bench where she removed all of his clothing. Standing one or two feet from the railing,

defendant picked Trayshawn up by one arm and one leg and swung him three or four times before letting

him go over the railing into the water. He was shouting "no mommy, no mommy," continuously as defendant

was swinging him.

Genesis 22:10-12 NIV: Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the LORD called out to him from heaven, “Abraham! Abraham!” “Here I am,” he replied. “Do not lay a hand on the boy,” he said. “Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.” My Interpreters Bible explains that the angel of the Lord is redactional for God, and thus He does intercede to derail this tragedy.

After leaving Twanda's, LaShaun took her children to San Francisco on BART, arriving in the city about 9:00 a.m. They walked from BART to Pier 7. About 3:00 pm she took the children to Pier 39 and bought them hot dogs from a street vendor. They then returned to Pier 7, where they walked around and her children played and watched people fishing.

Genesis 22:10-12 NIV: Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the LORD called out to him from heaven, “Abraham! Abraham!” “Here I am,” he replied. “Do not lay a hand on the boy,” he said. “Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.” My Interpreters Bible explains that the angel of the Lord is redactional for God, and thus He does intercede to derail this tragedy.

After leaving Twanda's, LaShaun took her children to San Francisco on BART, arriving in the city about 9:00 a.m. They walked from BART to Pier 7. About 3:00 pm she took the children to Pier 39 and bought them hot dogs from a street vendor. They then returned to Pier 7, where they walked around and her children played and watched people fishing.

Labels:

certitude and joy

Friday, February 24, 2012

große Oper in zwei Aufzügen!

I've come to the decision that my next production will be Die Zauberflöte von Mozart. This production will be identical to the original Die Zauberflöte, that is, the theatrical work written by Emanuel Schikaneder (see program to the left), the triumphant drama, and will be absolutely true to it in every respect, including all the words and instructions, characters and costumes, and will, as did the original, support the triumph of enlightened absolutism oner the evils of the obscurantists, most notably personified by the Q of the N, Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina. In sooth, in a quest for an absolute and a somewhat mercurial perfectionism, I have ordered my production assistant, the Rt. Hon. Mr. M___, to clone a copy of the Empress Consort (Holy Roman Empire) and Queen Consort (Germany) from a bit of bone marrow, a bit that I surreptitiously secreted from the Kapuzinergruft below the Capuchin Church on my last visit to Vienna, a trip whose necessary cover story was the yearly celebration of the new wine – the Sturm – but whose true raison was assumed through my intimate knowledge of the intimate pressings of the Masonic Temple Prostitutes, and thus realized by acts of which I may not be proud but were necessary nevertheless, in the service of art and its bounties.

I've come to the decision that my next production will be Die Zauberflöte von Mozart. This production will be identical to the original Die Zauberflöte, that is, the theatrical work written by Emanuel Schikaneder (see program to the left), the triumphant drama, and will be absolutely true to it in every respect, including all the words and instructions, characters and costumes, and will, as did the original, support the triumph of enlightened absolutism oner the evils of the obscurantists, most notably personified by the Q of the N, Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina. In sooth, in a quest for an absolute and a somewhat mercurial perfectionism, I have ordered my production assistant, the Rt. Hon. Mr. M___, to clone a copy of the Empress Consort (Holy Roman Empire) and Queen Consort (Germany) from a bit of bone marrow, a bit that I surreptitiously secreted from the Kapuzinergruft below the Capuchin Church on my last visit to Vienna, a trip whose necessary cover story was the yearly celebration of the new wine – the Sturm – but whose true raison was assumed through my intimate knowledge of the intimate pressings of the Masonic Temple Prostitutes, and thus realized by acts of which I may not be proud but were necessary nevertheless, in the service of art and its bounties.Well, OK, identical in all respects except for - I suppose it goes without saying - the replacement of the music, admittedly a hoary and bromidic element of the great work. I know that my adherence to the text and the meaning of the work may seem fetishistic, but truths are truths and thus must be given respect.

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Friday, January 27, 2012

Concerns and Annotations

Aspects of the libretto for the upcoming opera have raised some concerns among some of those who have read it or who have some knowledge of it. Those concerns come from the real event that it references, namely the death of the three children by their mother's hand. Does it represent the people, especially those people still alive, fairly or accurately? Might it hurt those people left behind, devastated by the tragedy?

I don't know. It's too great an event to capture in words or music. The reality is that I know nothing of the mother or her life, nothing of her inner world, nothing of her motivations or her communications with God, nothing of her relationship with her family or the events in their lives or the children or their father or anything. The libretto at most is just a fantasy, a concoction of my brain and its random associations of the few reported facts and some certainly misreported information with half-memories of my life and my prejudices and desires.

The writing was quick, a paroxysm of scribbling, multicolored, in a state, my breathing ragged and heavy, without editing. I can't really justify its point of view or claim it as my own, at least in a thoughtful sense. The writing of the libretto was the closest I have come in my artistic life to direct communication with the godhead, that divine stream that flows through us all. That direct link was a new experience for me, and I found it curious I could achieve this in writing words, when in writing music - my chosen art - it doesn't happen. For me, music has too much bookkeeping and too much intellect and too many details and decisions for it to flow freely out of my pen and spread itself across the page.

But, unthreading it all now, one can see where many of the words come from and, before one forgets, one should make note of these beginnings and directions and passes through one's neurological landscape. To follow along, one needs a copy of the libretto, which one can find here.

The opening line, as the footnote notes, is from Huxley, in particular the book pictured above. When I was a boy, I was believed to be gifted and I was placed in school programs designed for gifted and talented children. I basked in this appellation and believed in it or at least wanted it for myself. When I went to college, however, I discovered that there were people so far beyond me in intellect that I understood the reality of the quote. My geek friends said their clocks ran faster than ours, and I understood this to mean that there was no way to catch up to them, that their basic hardware was different than the rest of ours.

The second line is from Genesis 22. The Abraham and Isaac story looms large in the opera, a story that is bizarre and horrifying, as horrifying as the mother's tale, if one can get past one's Sunday School coloring book familiarity with it. There is no way to make sense of it, and even my 1950s copy of the 12 volume Interpreter's Bible begins its commentary pointing out that any man who thought of it, if his thoughts were detected, would be institutionalized, and any man who acted on it would be convicted and executed.

In reading the libretto, I see how much most of the story is me rather than the mother's: the tale of my sister's illness and the descriptions of my family, my take on Pascal and my high school friend's experiments, my reaction to hearing the story of the children, my reaction to reading the court documents, my thinking through it all while sitting at pier 7 as the day fades into evening. The libretto does not help the reader or the opera audience. It does not clearly label the edges of my story and the mother's, and they do mix frantically and fluidly. The character LaShaun, unlike the actual mother, is oftentimes saying or thinking things that I might say or think. Also, regardless of our command of the language, our thoughts are often profound, and because of this the LaShaun/Erling character sometimes slips into a highfalutin voice when representing his or her thoughts to us.

Some of the words do come directly from witness testimony, e.g., the child pleading 'no mommy' as he was thrown into the bay. But most of the words, like most of the text of the letter, and her prayer while killing the children, are my invention, except for a few bits cribbed from the Pascal Memorial. The death of the cat is the story of my cat, and the feeling of falseness in the world when the reality of death invades is something that I have felt and that many greater writers than me have related. Some bits after the murder are from the court documents, but even those are mixed up with my words and thoughts as well.

I notice, rereading the text, that are many threes, and I remember the use of threes in the score, in groupings and repeats and word painting, relating the deaths of Jesus and the two criminals on Calvary to the deaths of the three boys. Other biblical analogies appear: Jesus carried his wooden cross and Isaac carried the wood for his burning, so it is important that the boy carry something as well, but that's just a literary importance with no basis in fact.

I didn't know anything of the life that the mother had with the father, so the sex scene in the libretto has no relation to them, but is mine alone. I have felt what is described, the desire to merge with my partner but being stymied by the gap between us, and how we are all fundamentally alone, in life and especially in death. And, just to make sure it is clear, when she speaks of being left alone, and asking how He could leave her alone, this is an existential loneliness, and the pronoun He refers to God, the heavenly father of herself and her children, not the earthly father.

Society in general seems to have decided that the mother is crazy, and I've always wondered if one were crazy whether one would know. Would one have an inkling that something was wrong in one's thoughts? Would one reflect in one's own thoughts society's prejudices about craziness? I've heard something of the pain of insanity and this leads me to answer these questions in the affirmative. Thus the mother/Erling character in the libretto finds herself navigating the prejudices of craziness in herself. When her boy is sick he enters a delirium that describes a delirium I experienced when feverish with the measles as a child, and her desire to cool him in the water is my story, something I wanted.

The man with the Lorentz transformation tattoo is a friend of mine, a burning man campmate. The description of migraines is a combination of my experience, as I encountered the aura and still do; and the experience of my first wife Lynn, who had severe nauseating migraines throughout our entire marriage, each lasting several days, except during the period when she was pregnant. When vomiting forth this section, I remembered my mother telling me that Mormons believe that Mormon women will be eternally pregnant after death - a fancy interpretation of a passage in the Doctrine and Covenants - and thus the reference to pregnancy as a heavenly state.

The end of the story is me alone. When my current wife Lynne heard about the murder of the children, her immediate comment was that she hoped no one would ever cure the mother of her insanity, that the mother's bright, clear and sane knowledge of her actions would be too horrible a punishment. Those thoughts stayed with me throughout the piece, and especially the end.

I don't know. It's too great an event to capture in words or music. The reality is that I know nothing of the mother or her life, nothing of her inner world, nothing of her motivations or her communications with God, nothing of her relationship with her family or the events in their lives or the children or their father or anything. The libretto at most is just a fantasy, a concoction of my brain and its random associations of the few reported facts and some certainly misreported information with half-memories of my life and my prejudices and desires.

The writing was quick, a paroxysm of scribbling, multicolored, in a state, my breathing ragged and heavy, without editing. I can't really justify its point of view or claim it as my own, at least in a thoughtful sense. The writing of the libretto was the closest I have come in my artistic life to direct communication with the godhead, that divine stream that flows through us all. That direct link was a new experience for me, and I found it curious I could achieve this in writing words, when in writing music - my chosen art - it doesn't happen. For me, music has too much bookkeeping and too much intellect and too many details and decisions for it to flow freely out of my pen and spread itself across the page.

But, unthreading it all now, one can see where many of the words come from and, before one forgets, one should make note of these beginnings and directions and passes through one's neurological landscape. To follow along, one needs a copy of the libretto, which one can find here.

The opening line, as the footnote notes, is from Huxley, in particular the book pictured above. When I was a boy, I was believed to be gifted and I was placed in school programs designed for gifted and talented children. I basked in this appellation and believed in it or at least wanted it for myself. When I went to college, however, I discovered that there were people so far beyond me in intellect that I understood the reality of the quote. My geek friends said their clocks ran faster than ours, and I understood this to mean that there was no way to catch up to them, that their basic hardware was different than the rest of ours.

The second line is from Genesis 22. The Abraham and Isaac story looms large in the opera, a story that is bizarre and horrifying, as horrifying as the mother's tale, if one can get past one's Sunday School coloring book familiarity with it. There is no way to make sense of it, and even my 1950s copy of the 12 volume Interpreter's Bible begins its commentary pointing out that any man who thought of it, if his thoughts were detected, would be institutionalized, and any man who acted on it would be convicted and executed.

In reading the libretto, I see how much most of the story is me rather than the mother's: the tale of my sister's illness and the descriptions of my family, my take on Pascal and my high school friend's experiments, my reaction to hearing the story of the children, my reaction to reading the court documents, my thinking through it all while sitting at pier 7 as the day fades into evening. The libretto does not help the reader or the opera audience. It does not clearly label the edges of my story and the mother's, and they do mix frantically and fluidly. The character LaShaun, unlike the actual mother, is oftentimes saying or thinking things that I might say or think. Also, regardless of our command of the language, our thoughts are often profound, and because of this the LaShaun/Erling character sometimes slips into a highfalutin voice when representing his or her thoughts to us.

Some of the words do come directly from witness testimony, e.g., the child pleading 'no mommy' as he was thrown into the bay. But most of the words, like most of the text of the letter, and her prayer while killing the children, are my invention, except for a few bits cribbed from the Pascal Memorial. The death of the cat is the story of my cat, and the feeling of falseness in the world when the reality of death invades is something that I have felt and that many greater writers than me have related. Some bits after the murder are from the court documents, but even those are mixed up with my words and thoughts as well.

I notice, rereading the text, that are many threes, and I remember the use of threes in the score, in groupings and repeats and word painting, relating the deaths of Jesus and the two criminals on Calvary to the deaths of the three boys. Other biblical analogies appear: Jesus carried his wooden cross and Isaac carried the wood for his burning, so it is important that the boy carry something as well, but that's just a literary importance with no basis in fact.

I didn't know anything of the life that the mother had with the father, so the sex scene in the libretto has no relation to them, but is mine alone. I have felt what is described, the desire to merge with my partner but being stymied by the gap between us, and how we are all fundamentally alone, in life and especially in death. And, just to make sure it is clear, when she speaks of being left alone, and asking how He could leave her alone, this is an existential loneliness, and the pronoun He refers to God, the heavenly father of herself and her children, not the earthly father.

Society in general seems to have decided that the mother is crazy, and I've always wondered if one were crazy whether one would know. Would one have an inkling that something was wrong in one's thoughts? Would one reflect in one's own thoughts society's prejudices about craziness? I've heard something of the pain of insanity and this leads me to answer these questions in the affirmative. Thus the mother/Erling character in the libretto finds herself navigating the prejudices of craziness in herself. When her boy is sick he enters a delirium that describes a delirium I experienced when feverish with the measles as a child, and her desire to cool him in the water is my story, something I wanted.

The man with the Lorentz transformation tattoo is a friend of mine, a burning man campmate. The description of migraines is a combination of my experience, as I encountered the aura and still do; and the experience of my first wife Lynn, who had severe nauseating migraines throughout our entire marriage, each lasting several days, except during the period when she was pregnant. When vomiting forth this section, I remembered my mother telling me that Mormons believe that Mormon women will be eternally pregnant after death - a fancy interpretation of a passage in the Doctrine and Covenants - and thus the reference to pregnancy as a heavenly state.

The end of the story is me alone. When my current wife Lynne heard about the murder of the children, her immediate comment was that she hoped no one would ever cure the mother of her insanity, that the mother's bright, clear and sane knowledge of her actions would be too horrible a punishment. Those thoughts stayed with me throughout the piece, and especially the end.

Labels:

art,

beauty,

certitude and joy,

composition,

opera,

writing

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

The Rise of Sugary Snacks

Many have pointed to the impossibility of a pure culture, a culture untainted by others, a myth like that of the Aryan Race, whereas we know that clashes of culture, taking place in those rough boundaries between worlds, are the most fecund: lush contretemps where new growth arises. Even those attempts made by Hollywood and the English Language Popular Music Industry to bring the world under a single Novus Ordo, chanted under a bright yet monocolored flag of cultural hegemony, while successful in spreading their equivalents of Coca-Cola and the Frosted Flake to all corners of the world, have not ended the process, the ebb and flow, the mixing, the finding of the center and the unrefinéd tossing of flotsam at the edges.

Even we, we who fancy ourselves members of an elite art music establishment, are in fact sullied by all we hear and see and touch, the music and the noise and the screens and speakers everywhere that carry it all, a spray of seed that oft finds a fertile womb. We try to impose our rules, our concepts, our ideas of the future of music, but we find ourselves changed by the process, more affected than affecting.

But I do wonder why the aforementioned agents of cultural imperialism have been as successful as they have? Maybe, like the Frosted Flake, dripping with sugar, a mouth feel unmistakeable, a quick and agile crunch between the teeth, they are addictive. Maybe, like the Coca-Cola, we find that, after drinking quarts at a time, every day followed by every day, there is an itch, almost a burning in the back of our throats that water will no longer satiate. In a taxi in Ghana, I am listening to Bob Marley, and when I mention I am from California the driver says "West Coast! Tupac!" and I think how strange this is, but then I remember that I am here because my son plays in a Ghanaian drumming ensemble back home, and that those concerts are so much better attended than anything I have ever done, and again I wonder who is stealthfully and insidiously penetrating whom?

But I've finished the score for the new opera and am looking at a stack of them waiting to be delivered to the performers. Now that I am done, and I go through it, it surprises me. Where is the avant-garde boy I used to be? It's all so sweet, chords that my grandmother would have recognized as chords, and even the rhythmic complexities subtler than usual: a hemiola here and there, a confusing accent, a few meters flowing into others. Somehow I have been tainted by the songs of my youth, the poor imitations of sophistication and what we know to be the true delight that one has in great and high art, those fluff balls offered by my friends, pushed forward by the relentless pressure of the unseen and amorphous but so sharply felt peer group, a spear through the heart. But, on the other hand, just maybe I am in fact standing at an edge looking out over uncharted territory, some new veldt whose short grass will soon be replaced by another amalgam of this and that, all stolen from somewhere and everywhere.

Even we, we who fancy ourselves members of an elite art music establishment, are in fact sullied by all we hear and see and touch, the music and the noise and the screens and speakers everywhere that carry it all, a spray of seed that oft finds a fertile womb. We try to impose our rules, our concepts, our ideas of the future of music, but we find ourselves changed by the process, more affected than affecting.

But I do wonder why the aforementioned agents of cultural imperialism have been as successful as they have? Maybe, like the Frosted Flake, dripping with sugar, a mouth feel unmistakeable, a quick and agile crunch between the teeth, they are addictive. Maybe, like the Coca-Cola, we find that, after drinking quarts at a time, every day followed by every day, there is an itch, almost a burning in the back of our throats that water will no longer satiate. In a taxi in Ghana, I am listening to Bob Marley, and when I mention I am from California the driver says "West Coast! Tupac!" and I think how strange this is, but then I remember that I am here because my son plays in a Ghanaian drumming ensemble back home, and that those concerts are so much better attended than anything I have ever done, and again I wonder who is stealthfully and insidiously penetrating whom?

But I've finished the score for the new opera and am looking at a stack of them waiting to be delivered to the performers. Now that I am done, and I go through it, it surprises me. Where is the avant-garde boy I used to be? It's all so sweet, chords that my grandmother would have recognized as chords, and even the rhythmic complexities subtler than usual: a hemiola here and there, a confusing accent, a few meters flowing into others. Somehow I have been tainted by the songs of my youth, the poor imitations of sophistication and what we know to be the true delight that one has in great and high art, those fluff balls offered by my friends, pushed forward by the relentless pressure of the unseen and amorphous but so sharply felt peer group, a spear through the heart. But, on the other hand, just maybe I am in fact standing at an edge looking out over uncharted territory, some new veldt whose short grass will soon be replaced by another amalgam of this and that, all stolen from somewhere and everywhere.

Labels:

art,

beauty,

composition,

opera

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Pointing the way to the future of the medium

The life of the opera composer is a tough life, a life fabricated from raw ambition, of the ruthless climbing of the musical ladder, of finding a dog that will eat the other dog, of game-theoretic cuttings of the cake, delicate in an atmosphere of distrust, where one must watch so that even one's closest friends, smiling across the dinner table, sipping the wine that you will soon be buying for them, might consider, in a moment of inadequate attention, to just slip a knuckle dagger a-rib-glancing into your heart. But even in that dark and Bergmanesque life, sometimes a ray of sunshine breaks through, where for example, we replay the phone call that arrived on my doorstep this morning, transcribed here for your amusement:

PHONE

ring!

ERLING

looking at the caller ID

Oh is this the San Francisco Opera, oh my oh my, I can't believe it, you're commissioning one of my operas, oh god, oh god, I can't breathe, just a moment, you've made me so happy, give me a moment, while I compose myself, now, oh I'd like to thank my teachers, all those people who made this possible, I am so happy, wait, what's that, what?, I oh you what

PHONE

and we want to thank you for your past support

ERLING

oh no, my god no, you just want my money, oh the shame of it all, sniffling, then breaking into sobs, huh huh, chest heaving, why am I such a fool, a stupid fool, a fucking stupid worthless fool, piece of shit, fuck fuck fuck, oh god, fucking shit, that's the last of it, the last, oh god

PHONE

and this year we plan to bring back Turandot in a new production where Puccini himself appears on stage as a giant ice swan

ERLING

sobbing uncontrollably, lifts a gun to his head

GUN

bang!

...

Weeks after that aforementioned dinner conversation, my good artistic friend and competitor S. Kraft and I spent a pleasant evening in conversation, on display in a privacy booth at the 5M something-or-other-seasonal party. The atmosphere, thickened by the sweat of milling drunken youth, was redolent with sex, and our talk turned naturally to the topic. I told her of my previous as-yet-unrequited attempts to bring sex more strongly into my work, primarily through the vehicle of the long-suffering second Bisso-Wold collaboration 24x7, which, like Sub Pontio Pilato before it, had turned into a sprawling epic, caroming from Jack the Ripper to 120 Days of Sodom and points between. We talked of our shared admiration for San Francisco, a city of wantonness and hedonistic delight, where the fulfilling of one's lightest-felt caprices is the occupation of all. We spoke of the Armory, a beauteous Moorish Revival castle now run as a showcase to hogtying, a former boxing stadium now featuring girl-on-girl wrestling whose prize is the prising domination of the loser, and confessed of our friends who had worked there and throughout the sexual strata of the city.

I hoped, I said, to connect more with that institution, and maybe to perform something in its labyrinth of reconstructed motel rooms and gynecologist offices. I had considered scoring one of their works with a lush and voluptuous and eager composition, but recordings are not experience, and the fourth wall of film is too thick for such profound acts. Sex, I said, should be experienced live, either in the comfort in one's own homes, with one's own partners, or in public where that fourth wall cannot exist, where the distance of an audience member is difficult to maintain. Sex, performed live, is like a music that "sneaks past one's defenses and whose delicate beauty glides in just below the listener's critical consciousness," an act piercing direct to the emotional center, past the intellect, deep down and down and then down a little more.

So, soon, something will come of all this. In the meantime, there are two operas to finish, and one is the commission from the Austrians, appealing to my cupidity as well as my soul. And a commission from someone else, about which I had to sign a non-disclosure agreement, an agreement so tight that I had to agree that if approached by the media, I could in fact say nothing at all, not even "no comment" or "any other non-substantive answer." I list those possibilities now, again, for your enjoyment:

I hoped, I said, to connect more with that institution, and maybe to perform something in its labyrinth of reconstructed motel rooms and gynecologist offices. I had considered scoring one of their works with a lush and voluptuous and eager composition, but recordings are not experience, and the fourth wall of film is too thick for such profound acts. Sex, I said, should be experienced live, either in the comfort in one's own homes, with one's own partners, or in public where that fourth wall cannot exist, where the distance of an audience member is difficult to maintain. Sex, performed live, is like a music that "sneaks past one's defenses and whose delicate beauty glides in just below the listener's critical consciousness," an act piercing direct to the emotional center, past the intellect, deep down and down and then down a little more.

So, soon, something will come of all this. In the meantime, there are two operas to finish, and one is the commission from the Austrians, appealing to my cupidity as well as my soul. And a commission from someone else, about which I had to sign a non-disclosure agreement, an agreement so tight that I had to agree that if approached by the media, I could in fact say nothing at all, not even "no comment" or "any other non-substantive answer." I list those possibilities now, again, for your enjoyment:

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Mathematics, as it is

Whenever I am asked whether I make a living as a composer and I have to reveal that no, like so many, I have a day job, and then I'm asked what pray tell might that be, and I say I'm a mathematician or whatever category into which I'm dropping my job as Chief Scientist that day, I brace myself for the inevitable insight that well, Music is Mathematics, isn't it now. Being a Very Nice Fellow, I smile wanly and nod and then try patiently to explain that no, it is nothing like Mathematics, any more than Cooking is Mathematics, Writing is Mathematics, Painting is Mathematics.

But then, they might say, even those Things are in fact Mathematics. Remember the words to the children's song by Tom Lehrer:

But then, they might say, even those Things are in fact Mathematics. Remember the words to the children's song by Tom Lehrer:

Counting sheepWhen you're trying to sleep,Being fairWhen there's something to share,Being neatWhen you're folding a sheet,That's mathematics!

Like most children's songs, there is a great Truth here, which I capitalize to distinguish it from actual truth. Mathematics is a study of abstract objects, and most would understand that in the sense of modern Platonism: points, lines, ideals, manifolds, rings, lattices, graphs, numbers, cardinals, propositions, sets, symbols. Those abstract objects are fun to study in their own right, but the Truths of Mathematics come into their own and touch our lives when they find a life as models of Real Objects, some of which they model well and some of which they don't. Sometimes we work to arrive at those models, but oftentimes our conceptions of real objects are greatly simplified to match a mathematical theory that we happen to have lying about.

So, let's be more precise. What one might say is that those Fields of Study above have attributes that can be modeled more or less accurately by Mathematical Objects and that one might be able to glean certain knowledge of those Fields of Study by manipulating those Mathematical Objects, assuming all of one's assumptions are more or less correct, that the initial mapping is OK, and that those mappings still remain OK even under the effect of whatever manipulations one might make in the abstract realm.

What is really really hard about applying Mathematics to the Arts, is that manipulation of anything in the Arts might yield something interesting artistically, since there is no absolute arbiter of anything, as Good and Dad and Judgement are of the past, and one can find an audience for any jumble of phonons or photons or smell-ons. This makes the final judgement as to whether one's model is Right or Wrong well nigh impossible.

But still, limiting ourselves to the artistic area in question, one might ask: how well can available mathematical models map to something in Music that will help us compositionally or analytically? And, like all fields of study, there are some things that work OK: in my other life, the fields of acoustics and signal processing are based on this. In that day job, I may assume that a sound is modeled by a continuous curve and that I can differentiate and integrate and take limits to infinity. This assumption is far from a Truth, but it's OK, it works OK, I can manipulate all day long and at the end of the day discover something in my Platonist Plane of Existence that I can transcribe into software and drop into an iPad app and voila!, it sells to the masses who want Groupon coupons generated by listening to the ads on the TV. And, in my musical life, I may model a musical event as a note, and further reduce that to some parameters, like a pitch, which is then further reduced to a frequency, and that to a number which, in a ratio with other numbers, can inform me as to how to tune my guitar.

We all saw many attempts in the heady days of the post war academy to model musically related parameters like crazy, to manipulate them like crazy, and to come up with maps that we hoped we might follow to some Heavenly Abode where - well, I'm not exactly sure what. Where we might find the Perfect Music? Or the next Perfect Musical Publication? The serialists' attempts to construct a set-theoretic world based on a small set of discrete parameters is in my opinion a model-of-a-model far removed from the world of a sound, where it's hard enough to pin down music into discrete anythings, e.g. where a musical event starts and stops, or what its please-pick-one pitch is. If notes had single pitches, Auto-tune wouldn't exist. The funny thing is that there is a lot of fabulous serialist music, but, in my opinion, I don't think the models were helpful in getting there any more than any other kick in the pants.

Of course I know the models, and I use them, in a crafty way, to solve problems that I hit here and there, just like the Painter knows the models and may compute the Golden Ratio from time to time, not knowing whether it really is Good or Bad but whatever. And, if my inquisitor by this point hasn't run for the table with the potato chips, I would then set my hand on her shoulder and explain further that the joy of Music Composition, for me, is the impossible-to-quantify or at least the uninteresting-to-quantify ineffable aspects that I don't really even want to understand: how one writes when one has stayed up all night; how one allows God and his Angels, dark or light or their familiars, to speak through us; how it is that there is that one passage of Boulez's Le soleil des eaux that gives me chills; how I can find my way to a piece of music that, when listened to later, I don't understand in the slightest. There is an aspect of the endless, of eternity here, and I might remind my partner in conversation of the end of the B section of the tune above:

So, let's be more precise. What one might say is that those Fields of Study above have attributes that can be modeled more or less accurately by Mathematical Objects and that one might be able to glean certain knowledge of those Fields of Study by manipulating those Mathematical Objects, assuming all of one's assumptions are more or less correct, that the initial mapping is OK, and that those mappings still remain OK even under the effect of whatever manipulations one might make in the abstract realm.

What is really really hard about applying Mathematics to the Arts, is that manipulation of anything in the Arts might yield something interesting artistically, since there is no absolute arbiter of anything, as Good and Dad and Judgement are of the past, and one can find an audience for any jumble of phonons or photons or smell-ons. This makes the final judgement as to whether one's model is Right or Wrong well nigh impossible.

But still, limiting ourselves to the artistic area in question, one might ask: how well can available mathematical models map to something in Music that will help us compositionally or analytically? And, like all fields of study, there are some things that work OK: in my other life, the fields of acoustics and signal processing are based on this. In that day job, I may assume that a sound is modeled by a continuous curve and that I can differentiate and integrate and take limits to infinity. This assumption is far from a Truth, but it's OK, it works OK, I can manipulate all day long and at the end of the day discover something in my Platonist Plane of Existence that I can transcribe into software and drop into an iPad app and voila!, it sells to the masses who want Groupon coupons generated by listening to the ads on the TV. And, in my musical life, I may model a musical event as a note, and further reduce that to some parameters, like a pitch, which is then further reduced to a frequency, and that to a number which, in a ratio with other numbers, can inform me as to how to tune my guitar.

We all saw many attempts in the heady days of the post war academy to model musically related parameters like crazy, to manipulate them like crazy, and to come up with maps that we hoped we might follow to some Heavenly Abode where - well, I'm not exactly sure what. Where we might find the Perfect Music? Or the next Perfect Musical Publication? The serialists' attempts to construct a set-theoretic world based on a small set of discrete parameters is in my opinion a model-of-a-model far removed from the world of a sound, where it's hard enough to pin down music into discrete anythings, e.g. where a musical event starts and stops, or what its please-pick-one pitch is. If notes had single pitches, Auto-tune wouldn't exist. The funny thing is that there is a lot of fabulous serialist music, but, in my opinion, I don't think the models were helpful in getting there any more than any other kick in the pants.

Of course I know the models, and I use them, in a crafty way, to solve problems that I hit here and there, just like the Painter knows the models and may compute the Golden Ratio from time to time, not knowing whether it really is Good or Bad but whatever. And, if my inquisitor by this point hasn't run for the table with the potato chips, I would then set my hand on her shoulder and explain further that the joy of Music Composition, for me, is the impossible-to-quantify or at least the uninteresting-to-quantify ineffable aspects that I don't really even want to understand: how one writes when one has stayed up all night; how one allows God and his Angels, dark or light or their familiars, to speak through us; how it is that there is that one passage of Boulez's Le soleil des eaux that gives me chills; how I can find my way to a piece of music that, when listened to later, I don't understand in the slightest. There is an aspect of the endless, of eternity here, and I might remind my partner in conversation of the end of the B section of the tune above:

The answer is no, as Wittgenstein said in his Philosophical Remarks:If you could count for a year, would you get to infinity,Or somewhere in that vicinity?

Where the nonsense starts is with our habit of thinking of a large number as closer to infinity than a small one. ... The infinite is that whose essence is to exclude nothing finite.A model, no matter how finely developed, is, like the runner in Zeno's paradox, no closer to reality than the model before it. Music is not Mathematics, no how and no way.

Labels:

art,

beauty,

composition,

mathematics,

music

Saturday, October 15, 2011

A Celebration of Rejection; or the beautiful Miss Candy Candykins

I'm off to Paris to meet Lynne, check that her paintings match the city, and spread the ashes of our dear beloved friend Evelyn. A bit in the Seine, a bit at Les Deux Magots (sprinkled over the crème de menthe), a little buried outside her favorite pizza place, a little tucked in next to Napoleon in Les Invalides.

I'm off to Paris to meet Lynne, check that her paintings match the city, and spread the ashes of our dear beloved friend Evelyn. A bit in the Seine, a bit at Les Deux Magots (sprinkled over the crème de menthe), a little buried outside her favorite pizza place, a little tucked in next to Napoleon in Les Invalides.

After that, heading to Amsterdam to catch up with Laura Bohn, who is performing in a Monteverdi / Hip-Hop mashup performance, then to Berlin to perform the Shitstorm of Asshattery letter with the lovely and talented Candy (which may not be her real name). The highlight will almost certainly be my tearful love song to Simon Stockhausen, longing for the tête-à-tête we will now never have, which goes something like:

Dear SimonHow it thrills meWhen you sneerJust a littleCompel me to doWhat you want me to doI want to beA forward thinkerLike youMy SimonMy SimonMy Simon

So why I am traveling all the way to Berlin? I am making a big deal of a rejection, something we have to deal with daily, but, Oh what a rejection! A rejection of epic proportions!

On that topic, one of my peeviest peeves is as follows. One spends a lot of time working on a proposal asking some foundation for its cash, which, as far as I am concerned they owe you for chrissakes, or similarly on the preparations for a competition or reading, which again takes quite a bit of time and energy and a Benjamin or two for all the copying and postage and whatnot and then in the end, more often than not, you receive a form letter - well, just an email nowadays, akin to being dumped by SMS - which tells you very little, e.g.:

Dear Erling,

I am writing on behalf of Music Director Joana Carneiro to let you know that we have completed the selection for next year’s composers as part of Berkeley Symphony’s Under Construction new music reading series and, unfortunately, we are unable to offer you a position this year. We very much appreciate the strong quality of this year’s applicants and regret that there are but three positions available in the program. Thanks again for your interest in our program and we hope you’ll consider reapplying in a future season.

Yours sincerely,

--- so and so ---

Director of Operations

Berkeley Symphony

Work in progress

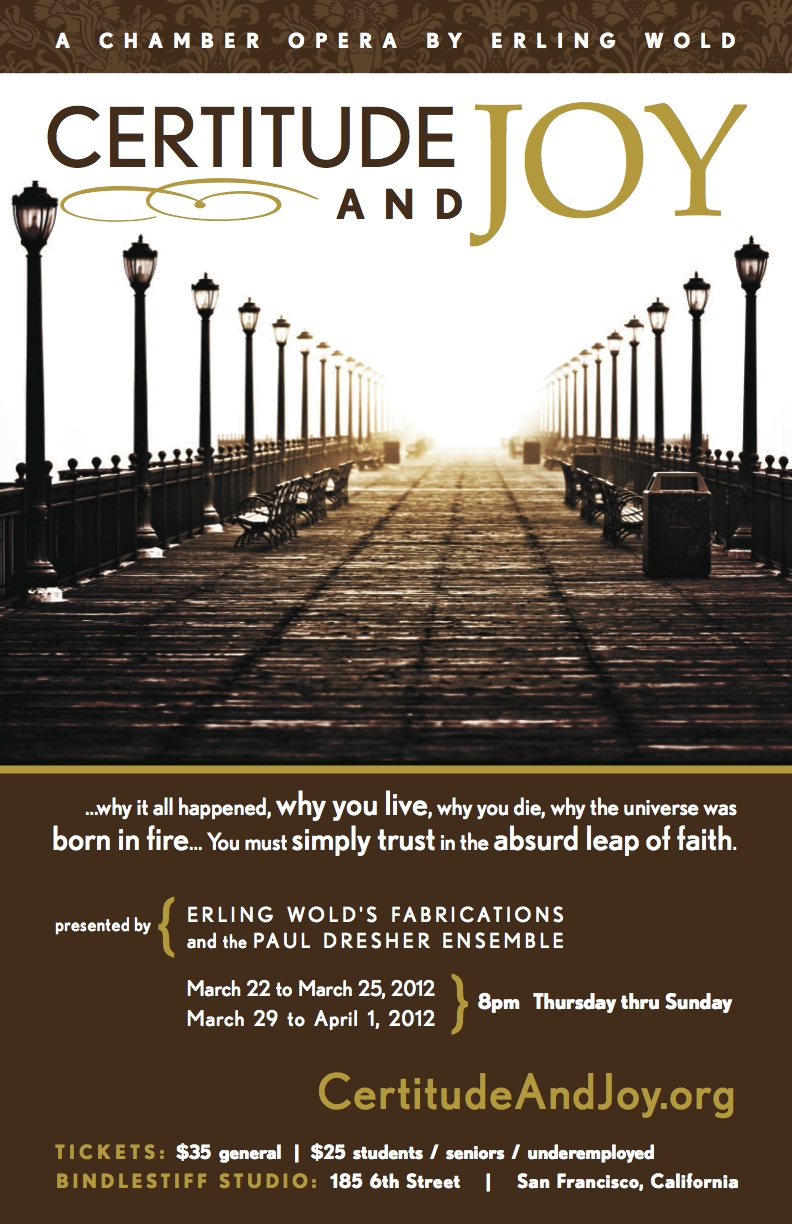

Working on the new opera, whose title has morphed into Certitude and Joy with various longish subtitles, and which is not to be confused with the orchestral piece of the same name, but which shares some of the same themes, especially the opening. In playing it for the wife and the director, the favorite section seems to be that whose accompaniment is an arithmetical average between two pieces: Regard du Père (Messiaen) and the introduction to the opera Irma (Gavin Bryars). It's a sentimental tune, sung by God to us the audience, describing his relationship to his prophets here on Earth.

Some of the words - especially the section about how one wishes to have it all explained at the end - is from my mother. She wants this, she hopes she will get it, but she is absolutely sure that she will meet my father after her death. On his deathbed, my father told me that his greatest wish was that his children had a personal relationship with Christ, a desire he didn't achieve. My mother wishes the same, but has accepted the loss.

Working on setting of the words, I'm reminded of a question put to me by Charles Shere once on stage, during a meet-the-composer moment after a performance of the opening of Sub Pontio Pilato in a two-piano reduction, viz Did you write the words before or after the music? I fumbled the answer, feeling there was something wrong with the question, that the right answer was something like Oh, they both came to me at the same instant or Oh, they both were developed together, walking hand in hand down the aisle to the perfect consummation of text and sound. I've realized since then that, as with everything else, there are no rules, every process is OK. I often work in all possible ways: music first, words second, vice versa, both together, each running ahead and waiting for the other to catch up, revisions and sketches and quick outlines and everything else.

Please remember this: there are no rules. There is good and bad, but there are no rules as to how to get there.

Some of the words - especially the section about how one wishes to have it all explained at the end - is from my mother. She wants this, she hopes she will get it, but she is absolutely sure that she will meet my father after her death. On his deathbed, my father told me that his greatest wish was that his children had a personal relationship with Christ, a desire he didn't achieve. My mother wishes the same, but has accepted the loss.

Working on setting of the words, I'm reminded of a question put to me by Charles Shere once on stage, during a meet-the-composer moment after a performance of the opening of Sub Pontio Pilato in a two-piano reduction, viz Did you write the words before or after the music? I fumbled the answer, feeling there was something wrong with the question, that the right answer was something like Oh, they both came to me at the same instant or Oh, they both were developed together, walking hand in hand down the aisle to the perfect consummation of text and sound. I've realized since then that, as with everything else, there are no rules, every process is OK. I often work in all possible ways: music first, words second, vice versa, both together, each running ahead and waiting for the other to catch up, revisions and sketches and quick outlines and everything else.

Please remember this: there are no rules. There is good and bad, but there are no rules as to how to get there.

Labels:

beauty,

certitude and joy,

composition,

opera,

words

Tonight's concert

In the first work, a plague-infested chipmunk, a cute little thing, as tiny as can be, with foam at the mouth, was hung in chains from the lighting grid, swinging slowly from side to side which, according to the program notes, was a reference to Reich's Pendulum Music. A small patch of hair on its chest had been shaved away, normally quite difficult to see, except that a small video camera was attached to the chain and the image from the camera was being wirelessly beamed to a large screen overhead. This allowed the audience and the humane society volunteers to monitor the condition of the expiring animal, both emotionally and physically. On the shaved portion of the skin, a small piezo microphone attached, and a long thin wire hung down, looping through some sort of magnetic amplification system, with the resultant enhanced bioacoustic signals - heartbeat, respiration et al - driving a solenoid which, in Rube Goldberg fashion, and, at the end of its extension, struck a percussionist quite hard just below the rib cage. At each bruising blow, the percussionist moved to the next event in the score, which was merely a list, viz:

In the first work, a plague-infested chipmunk, a cute little thing, as tiny as can be, with foam at the mouth, was hung in chains from the lighting grid, swinging slowly from side to side which, according to the program notes, was a reference to Reich's Pendulum Music. A small patch of hair on its chest had been shaved away, normally quite difficult to see, except that a small video camera was attached to the chain and the image from the camera was being wirelessly beamed to a large screen overhead. This allowed the audience and the humane society volunteers to monitor the condition of the expiring animal, both emotionally and physically. On the shaved portion of the skin, a small piezo microphone attached, and a long thin wire hung down, looping through some sort of magnetic amplification system, with the resultant enhanced bioacoustic signals - heartbeat, respiration et al - driving a solenoid which, in Rube Goldberg fashion, and, at the end of its extension, struck a percussionist quite hard just below the rib cage. At each bruising blow, the percussionist moved to the next event in the score, which was merely a list, viz:Hard mallet ff on bass drum, 4 cm from the edge, damped with a cupped hand.Later, after the show, I went into the lobby to ask John Luther Adams to autograph my copy of the orchestral score to Dark Waves. Skeptical at first, but then happy to find that I had actually purchased the score, rather than stealing from some music library, he sat down and began to work. Asking me whether there was an "H" in my name, I said yes, as there is: Erling Henry Wold, but unfortunately I misunderstood, and the very lovely dedication is now capped off by the name Ehrling Wold, bookending my J.S.G. Boggs Considerate States of America Banknote, whose signed REGISTER reads Earling H. Wold.

Medium triangle p rolled with beaters. etc

Labels:

beauty,

composition,

fandom,

music

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Shitstorm of Asshattery

I recently labored over an opera proposal with a fellow artist, a proposal submitted to a seemingly reputable operatic organization somewhere in a Central European country in response to their call for submissions. The theme of the call was The New Deal. We asked them if they meant by this the American New Deal, and they said yes. Our proposal made it through the first round of cuts and we were invited to give a full presentation, an invitation which we treated with all due diligence. We plotted and prepared for that day and, when it came, sent my colleague off to the wars armed with the sheafs of parchment upon which all was carefully lettered. We now join my colleague in her description of what transpired. As she prefers to remain anonymous, we will give her an appropriate pseudonym, say 'Candy', in the sequel.

Dearest Erling.

You got the short version earlier, which I wrote while I was doing that girl thing where some of us get so angry we have to either start ripping out throats or crying. Now I have perspective. Here is what happened:

About a week ago I started putting together my presentation, in the form of slides. They'd called a few times to ask whether I had any particular technological needs, or would require a piano, or whatever, and to tell me about the hardcore schedule they'd created for a full weekend extravaganza of meal tickets, free seats to see their very hyperactive rock musical with strong accidental homoerotic overtones about a group of lonely people and their relationships to their self-aware online avatars, group presentations, and so on. I'll send you a link to the presentation I eventually used, but it was basically images I found online and sound files and video clips (Chess Game and The Academy of Science) that would help me tell the story of what you do, what the project might be like, and what sort of vision we might be stumbling towards, with a bunch of text that I more or less stuck to. I thought about how to lead them through the thought process, how we interpreted New Deal and so on.

Yesterday we all met for an uncomfortable breakfast of soup bowls filled with coffee in the cafe downstairs from the theater, after which we all filed, 3 people at a time and standing very close together (the German stare, incidentally, is not lessened by proximity, in case you were wondering about that) via elevator up to the strange cluttered attic space upstairs where we would be presenting. We learned there had been 44 submissions this year. I also learned accidentally that at least one group... well, one guy... had been invited just a few days prior, to travel all expenses paid from Czechoslovakia. In fact I was the only local artist, everyone else of the 7 groups in the second round seemed to have come from a variety of exotic places.