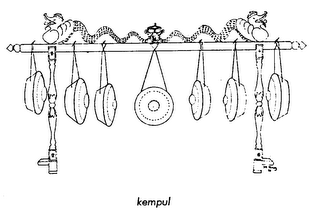

When I first started playing in a Javanese gamelan, it was difficult for me to get past the tuning, the unfamiliarity of which got in the way of understanding the music. In fact, it was so difficult for me in those first few days that that I didn't even get that I wasn't understanding the music. This was a little unexpected for me, as I was already very familiar with tuning experiments in modern classical music. For example, I had listened to a lot of quarter tone music and, at that time, I was working on a somewhat ridiculous piece, a concerto for contrabass accompanied by a trombone quartet and choir, where each section of the ensemble used a different fixed-pitch equal-temperament, e.g., chromatic scales of 1/8th tones and 1/6th tones and so on. The chorus was used like an orchestra, singing various IPA-notated phonetic abstractions. But I was raised on the serial music of the world of the post second Viennese school, was intimately familiar with the sound of it, had an intuitive grasp of it and this just seemed like a logical way to go forward. But the gamelan was different.

When I first started playing in a Javanese gamelan, it was difficult for me to get past the tuning, the unfamiliarity of which got in the way of understanding the music. In fact, it was so difficult for me in those first few days that that I didn't even get that I wasn't understanding the music. This was a little unexpected for me, as I was already very familiar with tuning experiments in modern classical music. For example, I had listened to a lot of quarter tone music and, at that time, I was working on a somewhat ridiculous piece, a concerto for contrabass accompanied by a trombone quartet and choir, where each section of the ensemble used a different fixed-pitch equal-temperament, e.g., chromatic scales of 1/8th tones and 1/6th tones and so on. The chorus was used like an orchestra, singing various IPA-notated phonetic abstractions. But I was raised on the serial music of the world of the post second Viennese school, was intimately familiar with the sound of it, had an intuitive grasp of it and this just seemed like a logical way to go forward. But the gamelan was different.My music at the time was not really harmonic, essentially percussion music with a pitch veneer slathered on top, disguising its true nature. I mean, it was harmonic in the sense that pitches were sounding at the same time as each other, and sometimes the harmonies were exciting and beautiful, but it wasn't really part of the overall architecture of the piece. So when I was confronted by music where the tuning was different but the music was straightforward - in the sense that it was not intended to be difficult to understand and was supposed to have an immediate emotional impact and leave you humming the tunes - the tuning was a wall that took a few days to get past. However, once I did, I fell in love with it, could sing along and could find the pitches easily and felt that they were, in fact, quite "correct." I wanted to comprehend this feeling and apply it in my own playground of pitches. I felt that I was missing something important and possibly following the wrong path.

The next surprise came, though, when I found that the gamelan pitches were not systematic. Each gamelan, while following some general guidelines about large and small intervals, was tuned quite differently. Bill Alves has a lovely set of graphs of tunings of some of the well-known gamelan from Central Java. The somewhat mythic story that was given to me by my teachers at the time was to the effect that, before a new gamelan was built, the builder would go sit on a mountaintop until the tuning came to them in an epiphanic moment, at which point they would build the first instrument and then copy the tuning of it for the others. I realized that my own experiments in tuning had been extremely constrained, in addition to having failed to arrive at any type of real "truth," whatever that might be. So my friends and I started building a lot of instruments with random tunings, cutting pieces of wood and metal to random shapes, laying them out in xylo/vibraphone-like arrangements in pitch-sorted order and then writing music using these pitches. It was amazed how quickly these random tunings sounded 'OK' and how they seemed intuitively to yield an appropriate music.

But, at the same time, I was discovering that the American gamelan builders were basically all using Just Intonation. Why exactly, given that the intuitive tunings of the Southeast Asian gamelan seemed like a possibly critical aspect of the whole music? Didn't this miss the point? I wasn't sure, but JI scratched my analytical mind's itch, that which was demanding some sort of organizational scheme for all the possible pitches. I had a little familiarity with it already. I had heard Harry Partch's music in my youth and I knew from my history of mathematics that solving the "problems" of JI had been a major preoccupation among the intellectual elite for a long time. I read Partch's book and I hooked up with the Just Intonation Network and this did help me get a handle on my pitch universe, or maybe I should say my interval universe. But, being an old dissonance guy and a sensation slut in general, I didn't get caught up in the pseudo-mystical nervousness about purity of intervals and the monotony of beatlessness. I liked the wolf tones, the odd intervals, the sweet edges of schismas and commas. And it didn't really deal with all my pitch issues anyway, e.g., glissandi and vibrato and the three strings on each key of the piano. (My JI friends' response to these issues? Don't use vibrato, don't use glissandi, don't etc etc.) (My noise music friends' response to everything I've been talking about? Who cares about pitches?)

The funny thing that happened on the way to this perfect universe of pitch complexity is that I started writing more and more tonal music. Thinking about intervals has a poisoning effect that way. It makes one think about roots and centers of intervallic grids. And then, in the end, I dropped the tunings and just found myself back in the usual world of more-or-less equal temperament. In the end, tunings were too socially isolating, too difficult given limited rehearsal times, too off-putting to the casual listener. My new opera, Mordake, is an all electronic piece and I could use any pitches I want, but I'm still shying away, fearing the impediment to the listener. It's hard enough to get people to listen; I don't want to make it more difficult for them. But then, maybe I should.